A slower output this week, last week, and probably next week as I work on drafting another lengthy author profile for Metropolitan Review; meanwhile here’s a quick note about something I noticed on Substack recently.

Setting the scene:

reviewed ’s novel, Major Arcana, in last week and caught shit from readers who said his prose was “purple” and “pretentious.”These are negative descriptors of qualities in Barney’s prose that’re just observably there: his sentences are extremely stylized and deliberately complex; the review also turns into a kind of manifesto about the need for this sort of writing.

You can quarrel with whether to call it “purple” vs “florid”—whatever.

Eye of the beholder.

Readers said some barbed things about Barney’s review, Barney said some barbed things back, and the whole exchange stayed in my head as I went around running errands over the weekend until I noticed the irony:

By creating a small scandal around his review of a Substack novel, he’s kinda fallen into one.

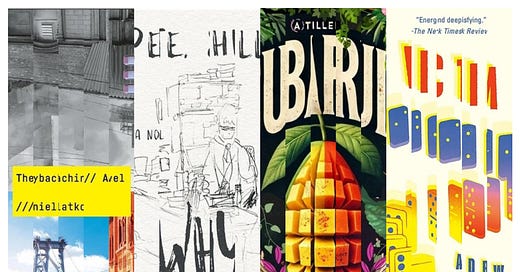

Wayback Machine is a satire, comedic throughout, but there are judicious flashes of real pain and heart to it. The protagonist is a bit of a loser and an asshole but he’s also painfully (discreetly) lonely; having lost the community that gave him so much meaning when he was younger, and his best friend having died just before he got out of prison, Nathan (protag) takes one huge, risky, bombastic shot at doing basically the only decent thing he can do: tell the story of the thing he cared about most, the thing that’s gone, that can’t speak for itself.

The protagonist of Wayback Machine believed in an institution (music), he saw real beauty and power in it, and then saw it get corrupted.

He knows there are people who don’t want him to say what’s on his mind, people who might destroy him if he does what he knows is right, but that’s exactly what he’s going to do.

Another popular Substack novel is

’s Why Teach? It’s about a young, earnest, affable English teacher, Will Able, who’s passionate about teaching literature, bonding widda yoots, but he’s told, by the administration, that there’s a new curriculum, and he has to fall in line with it: no more novels or plays in the classroom.They can only teach toward a standardized test.

The protagonist wants to teach Othello and The Crucible, he argues a case for their value and importance, but the administration simply tells him he’s got two choices: play along or get out.

The protagonist is a lonely guy, he feels like a bit of a loser, and he’s in this depressive/despondent period where he starts to think, The only thing I ever cared about was teaching literature to high schoolers, so that’s what I’m going to do; the drama is more a question of whether he’ll stand his ground, teach these things outright, and lose his job (thereby depriving students of the education), or if he’ll go along, pretend to comply with the new curriculum, and sneak a few meaningful things into it.

He knows there are people who don’t want him to say what’s on his mind, people who might destroy him if he does what he knows is right, but that’s exactly what he’s going to do.

Victim charts how a disgraced reporter rose to fame and success by making shit up, painting himself as both societal victim and social conscience.

It was all a lie.

The novel’s narrative is presented as a monologue/testimony/confession about what really happened. Peppered throughout are the author’s self-conscious remarks to a reader that, within this fictional universe, already knows him; he says he knows that we’re probably glad that he’s cancelled, and he knows we probably don’t want to hear from him right now…but he has to speak his piece.

He knows there are people who don’t want to sit and hear him say what’s on his mind, that he might only dig himself a deeper hole by speaking for what he knows is right, but that’s exactly what he’s going to do.

Feels relevant but tacky so I’ll be quick: my book Cubafruit came out this year and falls into a similar vein:

A reclusive Caro-like historian has been writing a multi-volume biography for 25 years. One day while sitting in the courtyard of an apartment/office complex, waiting to take one of the few telephone interviews of his career (which’ll be the most consequential), the biographer gets a call from an unlisted number. He answers and it’s a woman, hiding out on one of the zillion balconies overhead, aiming a rifle at him. She’s a survivor of the genocide that she claims his books have whitewashed. Now she wants to get looped into his interview and challenge him, live.

The novel’s framing action is the hourlong conversation/argument they’re having beforehand; they talk about the cross-section of history and biography, the ethics of telling one over the other…

It’s a conversation between two people who know that, under normal circumstances, neither would want to hear what was on the other person’s mind, but now they’re gonna speak their respective truths, even though—in doing so—there’s a good chance neither one of them walks away from it.

In light of that Vincenzo Barney review I noticed this trend, in Substack novels, where the main character is embattled by rhetoric. They’re seeking restitution or absolution or just inner peace by way of saying something that other people don’t want them to say; they usually end up in some position of having to defend why they’ve chosen their particular platform, medium, style, rhetoric—and I thought it was interesting (if not necessarily a signifier of anything) to see Barney, in the aftermath of his review, fall into a similar drama.

And guess what—I don’t care who knows it.

Something about Barney is really triggering to people! Was quite surprised by the amount of bullying he got.

I really liked your book, so please don't take this as a dig, but I think the trend you're picking up on is substack writers fantasizing about their writing being consequential, even if the consequences are negative. Speaks to an anxiety that they're basically shouting into the void.

Sort of the writer's equivalent of fantasizing about dying in a war.